The Green Book: Travel is Fatal to Prejudice

Green Book, this year’s Oscar winner for Best Picture, was loosely based on the true story of a friendship between an African-American concert pianist, Dr. Don Shirley, and his Italian-American driver and bodyguard, Tony “Lip” Vallelonga—a friendship that developed on the road during a concert tour through the “Deep South” in the 1960s.

While the story is moving and the acting superb, the movie and its audiences might have been better served if its eponymous inspiration had been given a more prominent role. Few people recognize the film’s title as a cinematic nod to the Negro Motorist Green Book—an indispensable ready reference source that many African-American travelers and motorists relied upon during the Jim Crow era.

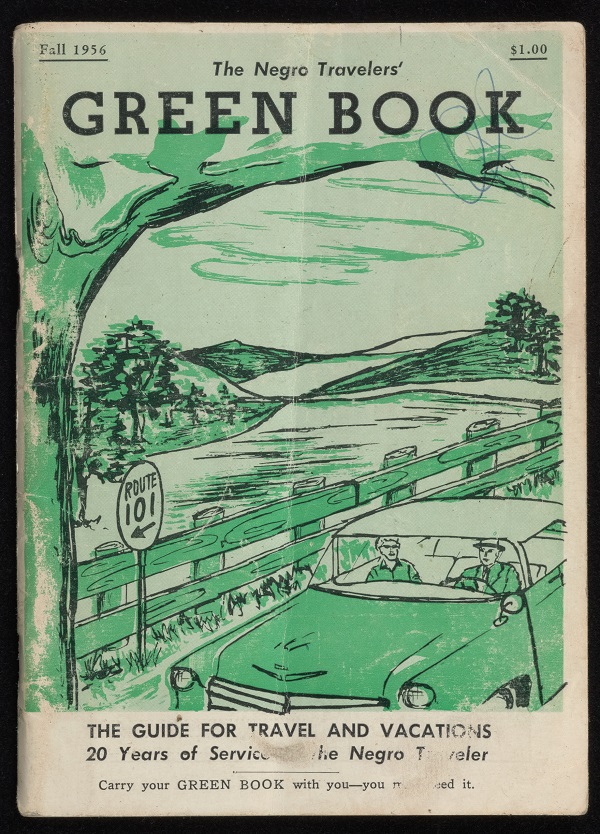

The film is set in 1962—more than a quarter of a century after the “Green Book” was first published by Victor Hugo Green, a New Jersey mail carrier living in Harlem. The Green Book, which was updated annually, contained travel tips, articles, and listings of hotels and other lodging, restaurants, nightclubs, gas stations, garages, salons, barbershops, and other businesses and establishments where African-Americans were known to be welcomed and served.

The Green Book provided a measure of protective reassurance and was designed to avoid or mitigate “embarrassing situations,” as Green himself put it, while also affording subtle commentary on the racial and social injustices of the time. For example, the same 1949 cover that cautions its readers to “Carry your Green Book with you—You may need it” also displays “Travel is Fatal to Prejudice,” a quote from Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad.

You can access digital versions of one of the largest collections of Green Books here, courtesy of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.